Πόσο θα διαρκέσει το ειρηνικό καλοκαίρι του Αιγαίου;

Ο αναλυτής Burak Bekdil*, σε άρθρο του στην ιστοσελίδα του BESA Center αναφέρεται στην συνάντηση του περασμένου Ιουνίου του Τούρκου Προέδρου,Ταγίπ ο Ερντογάν και του Έλληνα πρωθυπουργού Κυριάκου Μητσοτάκς , στις Βρυξέλλες, στο περιθώριο της επετειακής συνόδου του ΝΑΤΟ με στόχο να σπάσουν τον πάγο και να δημιουργήσουν μια θετική ατζέντα και για να διατηρηθεί ηρεμία στο Αιγαίο το καλοκαίρι.

Ωστόσο , υποστηρίζει ότι οι εκλογές του Ιουνίου 2023 ( στην Τουρκία) θα μπορούσαν να σημάνουν ότι το επόμενο καλοκαίρι στο Αιγαίο θα μπορούσε να είναι λιγότερο ήρεμο από αυτό το καλοκαίρι. Ο Ερντογάν είπε, σημειώνει, ότι θα προωθήσει την προεκλογική του εκστρατεία το 2022. “Είναι αρκετά προβλέψιμος ώστε να μπορούμε να περιμένουμε ότι θα επιστρέψει στον εκφοβιστικό, επιθετικό εαυτό του όσον αφορά την περιφερειακή πολιτική για την παγίωση συντηρητικών και εθνικιστικών ψήφων. Η Ελλάδα μπορεί να αποδειχθεί μόνο μία από τις πολλές χώρες που πρέπει να αντιμετωπίσουν τον συνήθη αντιδυτικό, φιλο-οθωμανικό, ρεβιζιονιστή Ερντογάν καθώς οι εντάσεις της εκστρατείας θερμαίνονται το επόμενο έτος”επισημαίνει ο Burak Bekdil.

Ωστόσο , υποστηρίζει ότι οι εκλογές του Ιουνίου 2023 ( στην Τουρκία) θα μπορούσαν να σημάνουν ότι το επόμενο καλοκαίρι στο Αιγαίο θα μπορούσε να είναι λιγότερο ήρεμο από αυτό το καλοκαίρι. Ο Ερντογάν είπε, σημειώνει, ότι θα προωθήσει την προεκλογική του εκστρατεία το 2022. “Είναι αρκετά προβλέψιμος ώστε να μπορούμε να περιμένουμε ότι θα επιστρέψει στον εκφοβιστικό, επιθετικό εαυτό του όσον αφορά την περιφερειακή πολιτική για την παγίωση συντηρητικών και εθνικιστικών ψήφων. Η Ελλάδα μπορεί να αποδειχθεί μόνο μία από τις πολλές χώρες που πρέπει να αντιμετωπίσουν τον συνήθη αντιδυτικό, φιλο-οθωμανικό, ρεβιζιονιστή Ερντογάν καθώς οι εντάσεις της εκστρατείας θερμαίνονται το επόμενο έτος”επισημαίνει ο Burak Bekdil.

Ο ίδιος επικαλείται, αν και δεν τον κατονομάζει, διπλωμάτη, ο οποίος πιστεύει ότι η Ελλάδα έκανε λάθος, όταν επέστρεψε στο τραπέζι των διαπραγματεύσεων, ενώ η Άγκυρα επιμένει σε λύση δύο κρατών στην Κύπρο. «Προφανώς ο Ερντογάν επενδύει σε έναν ήσυχο χειμώνα», είπε. “Μάλλον έχει δίκιο. Θα εξαρτηθεί από τη Δύση να καθορίσει μέσω κυρώσεων πόσο ο Ερντογάν θα απελευθερώσει τον εσωτερικό ισλαμιστή σταυροφόρο του το 2022-23″, καταλήγει ο Bekdil.

*Παρατίθεται στα αγγλικά το πλήρες κείμενο του άρθρου

Last summer, the Aegean Sea was in the midst of a dangerous tug-of-war. Turkey and Greece released one NAVTEX (navigational telex) after another. Ankara sent a survey vessel into the disputed continental shelf just 6.5 nautical miles off the Greek island of Kastellorizo. Turkish military figures suggested that Turkey could close the straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus to Greek and Greek Cypriot ships. And if that was not enough, in July 2020, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan converted Istanbul’s monumental sixth-century Greek Orthodox cathedral Hagia Sophia into a mosque.

As the standoff deepened, Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis convened his national security council. A statement issued after the meetings was reminiscent of pre-war times. “We are in complete political and operational readiness,” Minister of State George Gerapetritis said on state television ERT. “Most of the fleet is ready to be deployed wherever necessary.” In one dangerous incident on August 14, 2020, two warships, the Greek navy’s Limnos frigate and Turkey’s TCG Kemalreis, collided in the East Mediterranean.

All of that Turkish-Greek tension in the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas bolstered a century-long Turkish desire to take back some of the Greek islands. Yeni Şafak, a fiercely pro-Erdoğan newspaper, suggested that the Turkish military should invade 16 Greek islands.

In 1996, the Turkish and Greek militaries came close to a hot engagement on sovereignty claims over a tiny islet in southern Aegean sea. Twenty-four years after that conflict, in 2020, Metin Külünk, a former deputy from Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party, published a map of “Greater Turkey” that illustrated the extent of Turkey’s revisionist ambitions to include areas of Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Syria, Iraq, Georgia, and Armenia. In a similarly threatening statement, Turkish DM Hulusi Akar provocatively advised Greece to remain silent “so as not to become a meze [snack] for the interests of others.”

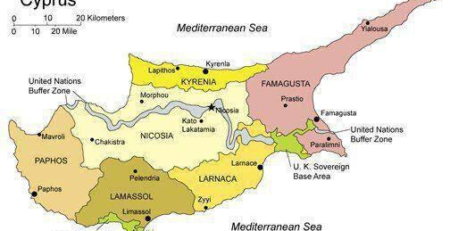

That much tension between two traditional rivals who had fought four conventional wars in the 20th century alone was enough to alarm the region, the EU, and the US. The EU threatened to sanction Turkey, and in September, Washington announced that it was partially lifting a 33-year-old arms embargo on (Greek) Cyprus, a move immediately condemned by Turkey.

By contrast, the summer of 2021 has seen fewer naval vessels on the Aegean Sea and a good deal less tension (so far).

In January, Turkey and Greece resumed long-suspended exploratory talks over territorial claims in the Mediterranean (Ankara and Athens held 60 rounds of talks from 2002 to 2016). There was little expectation that the NATO allies would miraculously reach peace in their 61st round of talks, but the fact of the talks should at least prevent further escalation.

In June, Erdoğan and Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis met in Brussels on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly and the NATO anniversary summit with the object of breaking the ice and constructing a positive agenda. Ibrahim Kalın, Erdoğan’s spokesman, and Eleni Sourani, director of Mitsotakis’s diplomatic office, will handle discussions from here in the hope of maintaining calm during the summer.

One motivator for both sides is the necessity for a peaceful tourist season. On June 14, Greek FM Nikos Dendias declared that Greece and Turkey would accept each other’s vaccination certificates. Tourist industry watchers interpreted this as a lifting of the long travel ban between the two countries (the Greek-Turkish border has been mostly closed since March 2020, barring a few exceptions). However, a month after Dendias’s announcement, maritime borders between Turkey and Greece remain closed.

How sustainable will the peaceful summer turn out to be? For Erdoğan, the primary reason for reining in his aggressiveness in the Aegean has been the threat of harsher Western sanctions amid Turkey’s ongoing economic descent. He feared, and still fears, that an augmentation of currently light EU and US sanctions might worsen Turkey’s ailing economy and eventually cost him his seat.

With inflation and interest rates already close to 20%, unemployment hurting more and more Turks, and hundreds of thousands of small businesses shut down as a result of the pandemic lockdown, Erdoğan is nervously calling the 2023 presidential campaign “an existential choice for Turkey.”

The election of June 2023 could mean that next summer on the Aegean could be less calm than this summer. Erdoğan has said he will gear up his election campaign in 2022. He is predictable enough that we can expect him to switch back to his bullying, aggressive self in terms of regional policy to consolidate conservative and nationalist votes. Greece may turn out to be only one of several countries having to deal the usual anti-Western, pro-Ottoman, revisionist Erdoğan as campaign tensions heat up next year.

“Nothing has much changed in substance [in Turkish-Greek relations],” said a prominent former Greek diplomat who had a top security portfolio. “The current relative calm is not to be credited to Turkey but to be debited to Greece [and its miscalculations].”

He said, “You fight battles on the battleground. You don’t fight by saying, childishly, that international law is on our side. You challenge power by power.”

The diplomat also thinks Greece made a mistake when it returned to the negotiating table when Ankara insisted on a two-state solution in Cyprus.

“Apparently Erdoğan has been investing in a quiet winter,” he said.

He is probably right. It will be up to the West to determine through sanctions how much Erdoğan will unleash his inner Islamist crusader in 2022-23.

Burak Bekdil is an Ankara-based columnist. He regularly writes for the Gatestone Institute and Defense News and is a fellow at the Middle East Forum.

* Τα ενυπόγραφα κείμενα απηχούν τις απόψεις των συντακτών τους

ΦΩΤΟ: Γραφείο Τύπου Έλληνα πρωθυπουργού