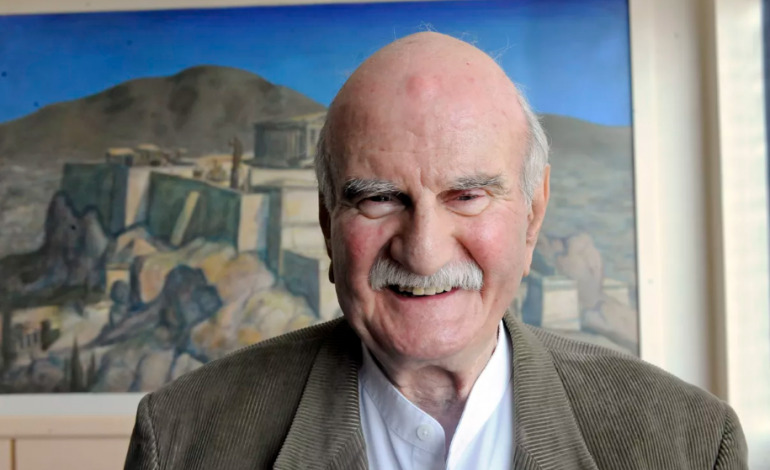

Πέθανε στα 97α του ο Χάρι Μαρκ Πετράκης, ο πιο σημαντικός Ελληνοαμερικανός συγγραφέας της γενιάς του

Όλο το συγγραφικό έργο του μιλά για τις δύσκολες στιγμές που βίωσαν οι Έλληνες μετανάστες που αναζήτησαν το αμερικάνικο όνειρο.

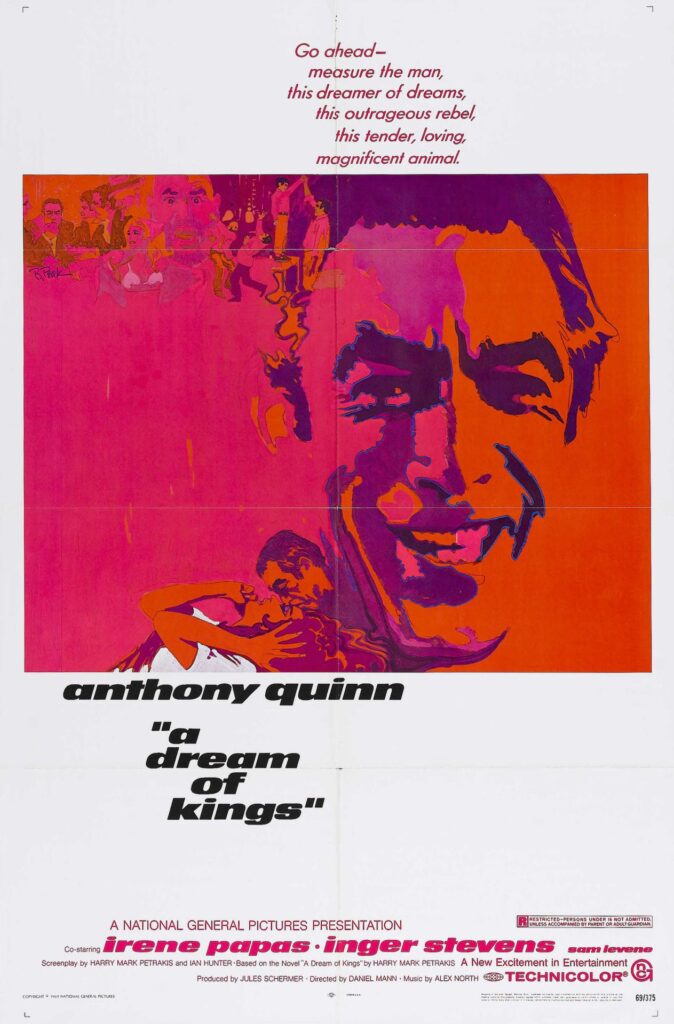

Ο Χάρι Μαρκ Πετράκης, ο πιο σημαντικός Ελληνοαμερικανός συγγραφέας της γενιάς του, πέθανε σε ηλικία 97 ετών. Είχε διαγράψει μία λαμπρή πορεία στον χώρο της λογοτεχνίας με 24 βιβλία, πολλά εκ των οποίων είχαν ως θέμα τη ζωή των Ελλήνων ομογενών στην Αμερική. Είχε τιμηθεί με τα βραβεία: Friends of American Writers Award, Friends of Litterature Award, Society of Midlands Author Awards και O Henry Award ενώ υπήρξε δύο φορές υποψήφιος για το Εθνικό Βραβείο Βιβλίου στις ΗΠΑ. Το 2013, τιμήθηκε με το Harry Mark Film Hellenes Award, για την ταινία «A dream of Kings (1969)» που είναι βασισμένη στο ομώνυμο βιβλίο του και μπήκε στη λίστα των Best Sellers των Ν.Υ. Times. Αξίζει να σημειωθεί ότι βασικός ήρωας του βιβλίου είναι ένας Έλληνας του Σικάγο, ενώ στην ταινία πρωταγωνίστησαν οι Άντονι Κουίν και Ειρήνη Παπά.

Οι New York Times έγραψαν για αυτόν ότι είναι «ένας από τους καλύτερούς μας συγγραφείς», ενώ ο βραβευμένος με νόμπελ Isaac Bashevis Singer έγραψε: «Ο Πετράκης είναι καλά νέα για την αμερικανική λογοτεχνία». Έχει διδάξει σαν Επισκέπτης Καθηγητής, καθώς και με βάση τη συγγραφική του ιδιότητα σε πολλά αμερικανικά πανεπιστήμια. Το 2004 το Αμερικανικό Κολέγιο Αθηνών τον βράβευσε σαν επίτιμο διδάκτορα στις Ανθρωπιστικές Επιστήμες. Αντίστοιχους τίτλους είχε πάρει και σε πολλά πανεπιστήμια των ΗΠΑ.

Ο Χάρι Μαρκ Πετράκης γεννήθηκε στην Αμερική το 1923, από Έλληνες γονείς που είχαν μεταναστεύσει το 1916 από το Ρέθυμνο στις ΗΠΑ. O πατέρας του εργάστηκε αρχικά ως ανθρακωρύχος στη Utah, ύστερα στο St. Louis όπου γεννήθηκε ο Πετράκης το 1923, και αμέσως μετά στο Σικάγο όπου και μεγάλωσε. Ο πατέρας του λειτουργούσε στον ιερό ναό των Αγίων Κωνσταντίνου και Ελένης. Όπως είχε ο ίδιος αποκαλύψει, όταν ήταν 11 χρονών προσβλήθηκε από φυματίωση, έμεινε αναγκαστικά για δύο χρόνια στο κρεβάτι με μόνη συντροφιά τα βιβλία. Έτσι γεννήθηκε το πάθος του για τη συγγραφή.

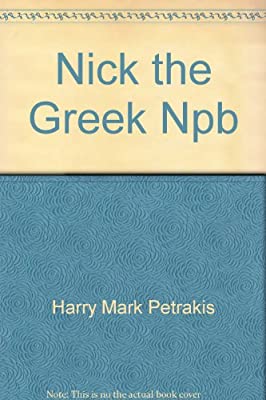

Το 1955 δημοσιεύτηκε η πρώτη του μικρή ιστορία, «Ο Περικλής στην 31η οδό» και το 1959 το πρώτο του μυθιστόρημα «Το λιοντάρι στην καρδιά μου”. Ακολούθησαν τα διάσημα μυθιστορήματα «Η Οδύσσεια του Κώστα Βολάκη» το 1963 και το μπεστ σέλερ «A Dream of Kings» το 1966, το «Νικ ο Έλληνας» το 1979 κ.α. Όλο το συγγραφικό έργο του Πετράκη μιλά για τις δύσκολες στιγμές που βίωσαν οι Έλληνες μετανάστες που αναζήτησαν το αμερικάνικο όνειρο. Μέσα από ρεαλιστικές ιστορίες αναφέρεται στις συνθήκες εργασίας των ανθρακωρύχων, στα ελληνικά εστιατόρια, ζαχαροπλαστεία, στις ελληνικές γειτονιές, αλλά και στην «αρνητική πλευρά» των ξενιτεμένων συμπατριωτών μας… στους απατεώνες, τους γκάνγκστερ, τους εθισμένους στον τζόγο.

O Αρχιεπίσκοπος Αμερικής κ. Ελπιδοφόρος έγραψε στο twitter: «Ο θάνατος του Χάρη Πετράκη, ενός διακεκριμένου λογοτέχνη και αγαπημένου συγγραφέα της Ομογένειας, είναι μια βαθιά απώλεια για την κοινότητά μας. Το έργο του θα εμπνέει και θα συντροφεύει τις επόμενες γενιές. Αιωνία η μνήμη του!»

The passing this week of Harry Mark Petrakis, a literary giant of the Omogeneia and a loving scribe of the Greek-American experience, is a profound loss to our community and to the world. But his work will endure for generations to come, even as his memory will be eternal! pic.twitter.com/4rLa5xSYLK

— Elpidophoros (@Elpidophoros) February 4, 2021

The Writer In Old Age

Harry Mark Petrakis

Novelist, short story writer, essayist and teacher

At my present age of 92, the afflictions of aging assail me like the onslaught of an army bent on my destruction. Each week seems to bring a new, unwelcome impairment. My chest rents space to a pacemaker, and I have several stents in my arteries. I have a spinal stenosis that restricts my reach and prevents me from putting on my stockings. Add to that a peripheral neuropathy that causes burning in my toes and numbness in my fingers, making it difficult for me to button my shirt. I also have chronic digestive problems and an insidious fatigue. Not long after I rise in the morning I yearn to recline on the couch.

If I live a few years longer, I will enter the realm of Gero Panakis, who I remember as a boy to be the oldest member of my father’s parish. While no one could be sure, it was rumored the old man was near 100. I remember him after he had received the sacrament of Communion, lurching down the center aisle in church, bent double as he walked, limbs trembling, cheeks twitching, his carcass withered, worn-out, fossilized. As he passed the pew where I sat, a wrenching at my nostrils confirmed he also smelled like a goat. God spare us such length of life!

What faculties do I now retain? I can still walk (with the aid of a cane), still talk, eat, sleep (with the aid of pills), smile and (on occasion) laugh. Most thankfully, I am still able to fashion words together to make stories. I am no longer confident enough to start a book-length novel but I do manage essays and short stories.

Yet while sitting at my computer and fashioning my stories, resisting an urge to lie down, I cannot help plaintively remembering the years of my creative vigor when my body and spirit jubilantly embraced the strain and rigors of writing. A short story could be written in several days to a week. A novel took from a year to three years. Yet in the heat of creating, time seemed inconsequential, a week passing as if it were a day.

For a three-year period in the mid-1970s, while I was working on “The Hour of the Bell,” my historical novel on the 19th-century Greek War of Independence, I remember how I’d wake eager to work and, in the evening, regret having to stop.

My day would begin with a light breakfast of coffee and a muffin. Afterwards, I’d ascend to my study, a magnificent, high-ceilinged room set in a rainbow of sand dunes, thickly foliaged fir and pine trees and a boundless panorama of water. That lake view ranged from serene to turbulent and in color from cerulean blue to shades of light gray. I’d raise one of the blinds and permit myself a brief look at the splendor of the emerging day. Then I’d lower the blind again quickly as a precaution against the lure of daydreaming. I sat down at my desk feeling myself a cauldron of energy ready to detonate.

I was still writing on an electric typewriter then, and in the hours that followed there would be fitful starts and stops. Revisions then required a page of paper withdrawn and a new page inserted. Bond in different colors designating different drafts mounted in piles at the corner of my desk.

A book began slowly, with uncertainty. Fearing false starts and treacherous detours, I carefully felt my way. As the manuscript lengthened, the stacks of pages building, the characters becoming more fully formed, a greater confidence in the unfolding story developed. Through the months into years of writing that followed, nurtured by a regular daily routine, a rhythm of writing took over. Sentences and paragraphs began to interweave effortlessly. A harmony between writer and writing was achieved. The writing began to emerge with such resilience and fluidity I could not help feeling myself a conduit from some wellspring of boundless power. A poet whose name I cannot recall referred to those periods of creativity as “taking God’s dictation.”

That creative force and excitement kept me at my work for 10, 12 hours at a time. When I did break briefly for lunch or dinner, I carried the resonances of writing with me. At the table with my wife and our sons I felt strangely disembodied, their voices coming to me as from a great distance.

When I finally went to bed, curled beside my wife, sleep eluded me. My mind swirled with the faces and voices of my characters, with the skeletal structuring of still unwritten scenes. After I had fallen asleep, the characters in my book invaded my slumber, playing out scenes already written or still unwritten.

For those months that I wrote, the world of my book consumed my life. The hours I spent away from the work were fretful and restless, fragmented between fantasy and reality. I had become a man with a fever, fully functioning only when I was writing. That was the way it used to be. Then there is the way it is now.

Yet I know I am not alone. As I age, so do multitudes. The musician with diminished hearing, the artist with fading sight, the actor with slurring speech, the athlete with faltering strength. All living things experience such loss. And each human being must find a way to cope with that decline.

In the end, despite my expiring body and my lamenting about how it was once, I must be grateful that in a world where the moment we are born we are old enough to die I have been allowed to live 92 years. I have a wife who has been lover and companion now for more than 70 years still beside me. People cannot mention the name of one of us without, in the same breath, speaking the name of the other. We have good, loving sons and grandchildren and a great-grandchild. We have battled adversity, overcome frailties, and I have written my books. Kurt Vonnegut said that, for a writer, writing one’s books and having one’s children should be enough and we should not be greedy. Yet we have had much more, including durable friendships and travel across the world. With all human flaws, we have lived abundantly fulfilling lives that we will carry into eternity.

I need now to be prepared for death without brooding about death. I need to try to put remorse and regrets aside, to temper my hopes, to remember daily to be tolerant and kind to those whose lives touch mine. Above all I need to continue my daily struggle to harness my waning spirit and body and endeavor to put words together to make sentences, and to fashion those sentences into stories. There is no saner way for an old writer to end his days.

Περισσότερες πληροφορίες: https://www.harrymarkpetrakis.com/