Οι εφημερίδες The Washington Post και The Times για την Αγία Σοφία

Διαβάστε πιο κάτω δύο άρθρα για την μετατροπή της Αγίας Σοφίας σε τέμενος, που δημοσιεύτηκαν στις έγκυρες εφημερίδες “The Washington Post” και “The Times”.

![]()

| By Ishaan Tharoor with Ruby Mellen |

The trouble with making Hagia Sophia a mosque again

| People celebrate outside Hagia Sophia in Istanbul on July 12. (Erdem Sahin/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock) |

Like a vaulted dome, the status of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia — the byzantine cathedral turned Ottoman mosque turned preeminent global tourist destination — has long hung over the rule of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. For a leader who has championed the steady reassertion of his nation’s Islamic heritage, restoring Turkey’s most famous site of worship to the Muslim faithful would be a powerful legacy.

There were clear reasons to avoid the temptation. Hagia Sophia, built by the Emperor Justinian I in 537, was once the largest and grandest church in all of Christendom and remains at the spiritual heart of Orthodox Christianity. “It was converted into a mosque in 1453, when the Ottomans conquered Istanbul, with minarets placed around its perimeter, its byzantine mosaics covered in whitewash,” wrote my colleague Kareem Fahim. But in its shadow, there existed large and prominent Greek and Christian communities throughout what is now Turkey.

In the bloody chaos that followed the Ottoman Empire’s collapse, many of those communities disappeared. At the same time, the modern Turkish republic sought to move beyond its Ottoman cultural moorings. A 1934 decree by Turkey’s secularist modern founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, made Hagia Sophia into a museum that commemorated the depth of its history, which predates the advent of Islam. It became a monument to a universal legacy that transcends religion and underscored Istanbul’s place at the heart of different cultures and faiths. In the past decade, less famous former churches in other parts of Turkey — some also named Hagia Sophia — have resumed services as mosques, but Erdogan and his allies still shied away from claiming their greatest prize.

Until Friday, when the Turkish president announced that Hagia Sophia would be a mosque again, with Muslim prayers resuming in the compound in two weeks. Turkish officials said the site would remain open to all and that its Christian icons and mosaics would not be damaged.

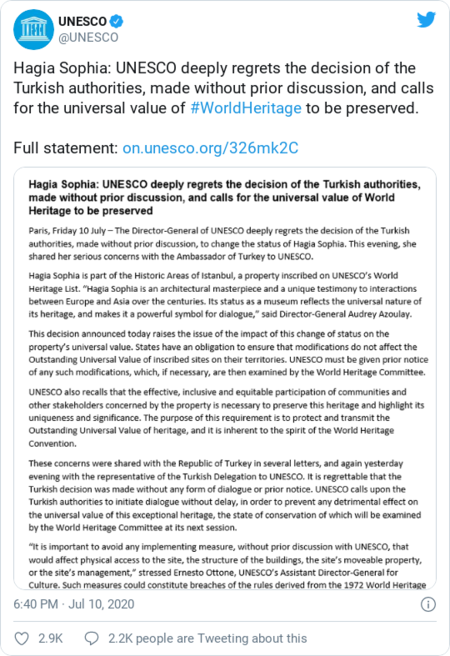

A global backlash nevertheless came. Russia’s Patriarch Kirill branded the move a “threat to the whole of Christian civilization.” On Sunday, Pope Francis declared that he was “thinking of St. Sophia” and was “deeply pained.” UNESCO, the United Nations’ cultural agency, released a statement warning Turkish authorities against “taking any decision that might impact the universal value of the site.” Governments from neighboring Greece to the Trump administration to the Kremlin issued notes of concern and protest.

Some critics lamented what they saw as a blow to Turkish secularism. “To convert it back to a mosque is to say to the rest of the world unfortunately we are not secular anymore,” Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk told the BBC on Friday. “There are millions of secular Turks like me who are crying against this but their voices are not heard.”

Political rivals harped on the timing of the act, as Erdogan reckons with a tanking economy that has been further ravaged during the coronavirus pandemic. “This is a world legacy, a magnificent work,” Ekrem Imamoglu, the mayor of Istanbul and a member of Turkey’s largest opposition party, said in an interview last month before Friday’s announcement. “What is the need to open this debate now, when 97 percent of tourism has frozen, while hotels are closed, while tourism has plummeted and hundreds of thousands of people have become unemployed?”

Erdogan has shrugged off complaints, framing the decision as an exercise of Turkish sovereignty. The country’s opposition parties haven’t made too much of a fuss. “Turkey is a country where religion and nationalism intersect, so that many of the staunchly anti-Erdogan camp would back the principle of Turkish sovereignty over the monument,” observed Louis Fishman, a professor at Brooklyn College. “Upholding that prerogative absolutely would trump the debate of whether Hagia Sophia should be a museum or a mosque.”

(Ozan Kose/AFP/Getty Images)

Hagia Sophia is hardly the first historic religious site to fall afoul of modern politics. India still bears the scars of the 1992 religious riots that followed a mob’s demolition of a medieval mosque that some Hindus believed was built atop the birthplace of a major deity. The conflict over the site has long been weaponized by the country’s current Hindu nationalist rulers. For Erdogan, changing Hagia Sophia’s status appears to be a move to appeal to his base and assert his political brand — a strident nationalism inflected by his religiosity that anchors itself in a decades-old ideological struggle with more secular Turks.

“As a museum, the Hagia Sophia symbolized the idea of there being common artistic and cultural values that transcended religion to unite humanity,” Turkey scholar Nicholas Danforth told Al-Monitor. “Its conversion into a mosque is an all too appropriate symbol for the rise of right-wing nationalism and religious chauvinism around the world today.”

Turkey’s Christian population, meanwhile, is a bystander to a debate that ultimately ignores the challenges facing a shrunken community. “It is not about us, neither the agendas to convert it to a mosque nor loud reactions against it in Turkey or abroad,” Ziya Meral, director of the Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research in Britain and a Turkish Christian, told Today’s WorldView. “If it was, the focus would have been on how we can protect the future of some 100,000 or so Christians left in the country, and the tragedy we mourn would have been why so many of our churches are empty and why in a few decades Anatolia’s rich Christian heritage will not have much by way of living cultures and communities.”

The Times view on Hagia Sophia: Secular Retreat

President Erdogan’s decision to turn Hagia Sophia into a mosque has dismayed allies

Mustafa Kermel Ataturk’s move in 1934 to turn Hagia Sophia from a mosque into a museum was a symobolic moment. The founder of modern Turkey saw it as an opportunity to affirm his country’s commitment to secularism and its reliability as a western ally. The announcement on Friday by his successor, Recep Erdogan, turning the ancient building back into a mosque, following a court ruling earlier that day that overturned the decision of 1934, is a symbolic moment too, albeit one that is far more unsettling for the west. It is a sign of the extent to which Turkey under Mr Erdogan has embraced religious nationalism and of its disdain for the sensitivities of its allies.

Hagia Sophia is listed by Unesco as a world heritage site. The vast, domed building was built by the Emperor Jusitinian in the sixth century as the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople and for centuries, visitors to Instanbul were dazzled by its beauty. It was briefly converted into a Catholic cathedral in the 13th century. But following the Ottoman conquest in 1453 it was used as a mosque. Its remarkable mosaics and frescoes were whitewashed over to comply with the Islamic ban on figurative art and were only uncovered in the 20th century. These days Hagia Sophia is Istanbul’s leading tourist attaction, drawing 3.7 million visitors a year.

Although Mr Erodogan is a religious conservative, his own conversion to the campaign to have Hagia Sophia turned back into a mosque is relatively recent. Until last year he had never spoken publicly in favour of it. His change of heart coincided with a downturn in his political fortunes. His poll numbers have plummeted. Last year his AKP party lost municipal elections in his former stronghold of Instanbul. Meanwhile, new breakaway parties from the AKP threaten to draw support from the religous right. At the same time, the economy is in the midst of its second recession in two years. In this context, last week’s decision made for good domestic politics, allowing Mr Erdogan to paint opponents as unpatriotic.

Yet the price of domestic success is likely to be paid in the form of fresh strains on Turkey’s external relations. The move has added to tensions with neighbouring Greece, where the Hagia Sophia is regarded as an important symbol of Hellenic culture. The move has also drawn condemnation from the primate of the Russian Orthodox Church which said that the conversion would “inflict great pain on the Russian people”. It has also been crticised by the US government. A particular concern now will be the fate of the frescoes which are protected under Unesco rules.

More broadly, Turkey’s western allies will be nervous as to where Mr Erdogan’s latest turn towards religious nationalism might lead next. Since thwarting a coup attempt in 2016, he has shored up his position with large-scale purges and constitutional changes — narrowly ratified via referendum in 2017 — that give him almost unbridled executive power. At the same time, he continues to drift ever further from the ideals of Ataturk’s secular state. In the past months, four opposition MPs and two journalists have been arrested on espionage and terrorism charges, while opposition TV channels have been slapped with broadcasting bans. Turkey remains a Nato member and it is in the west’s interests to try to keep it as an ally in a strategically volatile region. But Mr Erdogan has sent a powerful signal that it will be on his terms.