Απαραίτητος ο ρόλος της Κύπρου στη Μεσόγειο

Την σχέση του Κυπριακού με την γωγραφία επιβεβαιώνει σε άρθρο της η Caroline D. Rose, η οποία τονίζει ” Η τοποθεσία και οι φυσικοί πόροι του νησιού το έχουν καταστήσει στόχο φιλόδοξων γειτόνων και αντίπαλων δυνάμεων”. Βεβαίως, αναφέρει η Rose , το Κυπριακό εξακολουθεί να καθορίζει τις Τουρκο-Ελληνικές σχέσεις. “Όμως το νησί βρίσκεται επίσης στο επίκεντρο άλλων θεμάτων της περιοχής. Έχει καταστεί κεντρικό σημείο εκκίνησης για τις επιχειρήσεις της Δυτικής νοημοσύνης, της στρατιωτικής και της αντιτρομοκρατίας στη Μέση Ανατολή. Βρετανικές βάσεις στην Κύπρο έχουν μετατραπεί σε μια πύλη από την οποία οι ΗΠΑ και το ΝΑΤΟ μπορούν να ξεκινήσουν αεροπορικές αποστολές, να παρακολουθούν τις ηλεκτρονικές επικοινωνίες, τα σήματα πληροφοριών και τις ναυτικές επιχειρήσεις. Έχει επίσης συμμετάσχει σε κοινές ναυτικές ασκήσεις με μέλη του ΝΑΤΟ όπως η Γαλλία, η Ιταλία και οι ΗΠΑ στη Μεσόγειο”, παρατηρεί.

Επίσης, επισημαίνεται :

*Με νέες ανακαλύψεις και αλλαγή των εθνικών προτεραιοτήτων, ο ανταγωνισμός για την Κύπρο εξελίχθηκε με την πάροδο του χρόνου. Όμως η δυναμική στην Κύπρο έμεινε λίγο πολύ η ίδια: Παραμένει ένα μικρό, κατακερματισμένο νησί, το οποίο παλεύουν οι ηθοποιοί που επιδιώκουν να επεκτείνουν το στρατηγικό τους βάθος στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο.

*Με νέες ανακαλύψεις και αλλαγή των εθνικών προτεραιοτήτων, ο ανταγωνισμός για την Κύπρο εξελίχθηκε με την πάροδο του χρόνου. Όμως η δυναμική στην Κύπρο έμεινε λίγο πολύ η ίδια: Παραμένει ένα μικρό, κατακερματισμένο νησί, το οποίο παλεύουν οι ηθοποιοί που επιδιώκουν να επεκτείνουν το στρατηγικό τους βάθος στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο.

Διαβάστε αναλυτικά το άρθρο:

By: Caroline D. Rose

In 1956, Cyprus found itself at the center of a heated debate in the United Kingdom. Amid the growing push for independence on the island, which had been a crown colony since 1925, London was accused at home and abroad of repressing the Cypriot people’s right to self-determination. Prime Minister Anthony Eden tried to make the case that maintaining control of Cyprus was in Britain’s interest, saying in a speech on June 1, 1956, that without Cyprus the U.K.’s access to oil would be jeopardized, and without a reliable supply of oil, the country would see a spike in unemployment – even hunger.

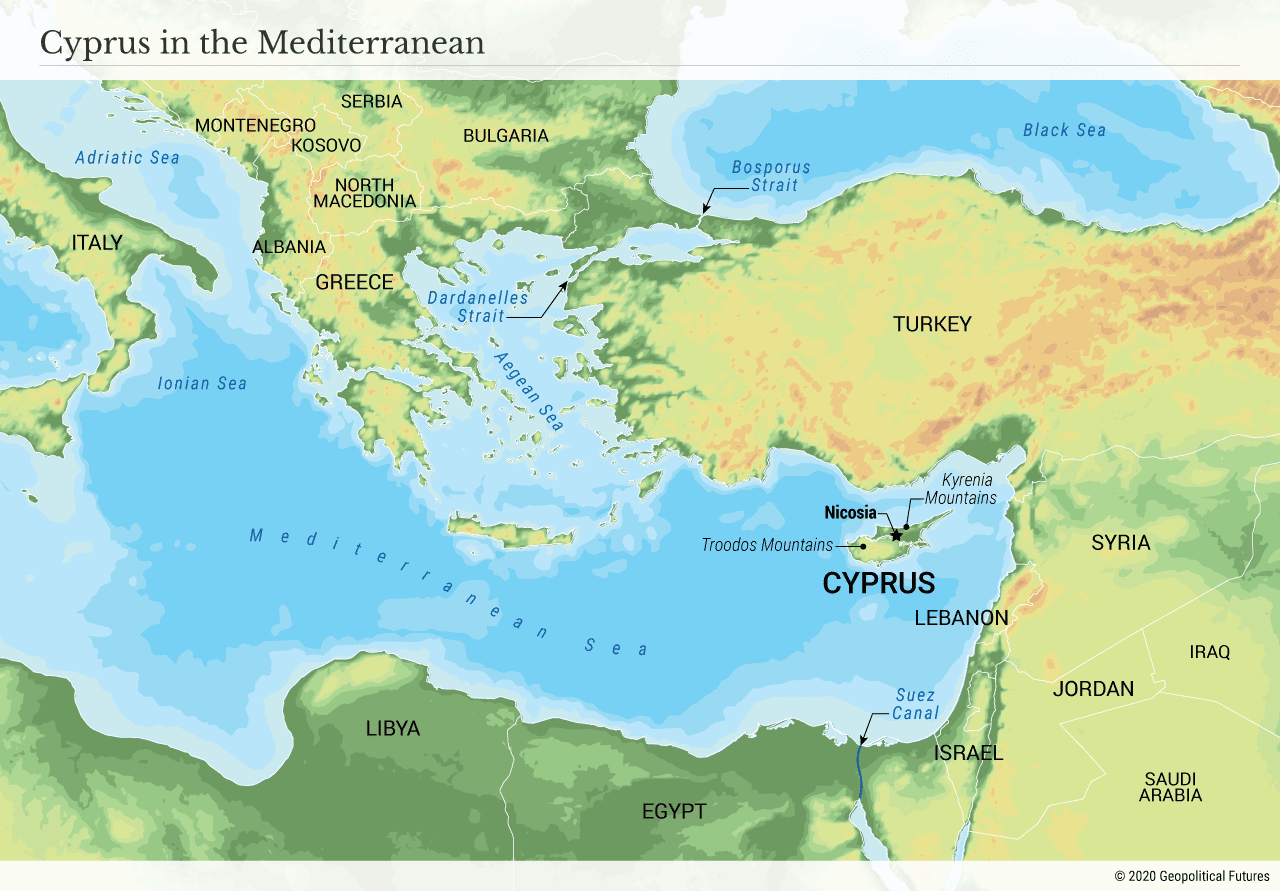

Nearly 70 years later, Cyprus continues to play a pivotal role in the foreign policies of Mediterranean and global powers clamoring for influence over the strategically located island. Throughout its history, it has been occupied by numerous empires and countries, and today, great powers like the U.S., Russia and Turkey as well as European states are trying to gain a foothold there. How has a small Mediterranean island attracted so much attention from so many powerful players? The answer lies in its geography, location and natural resources.

A Target for Rivals

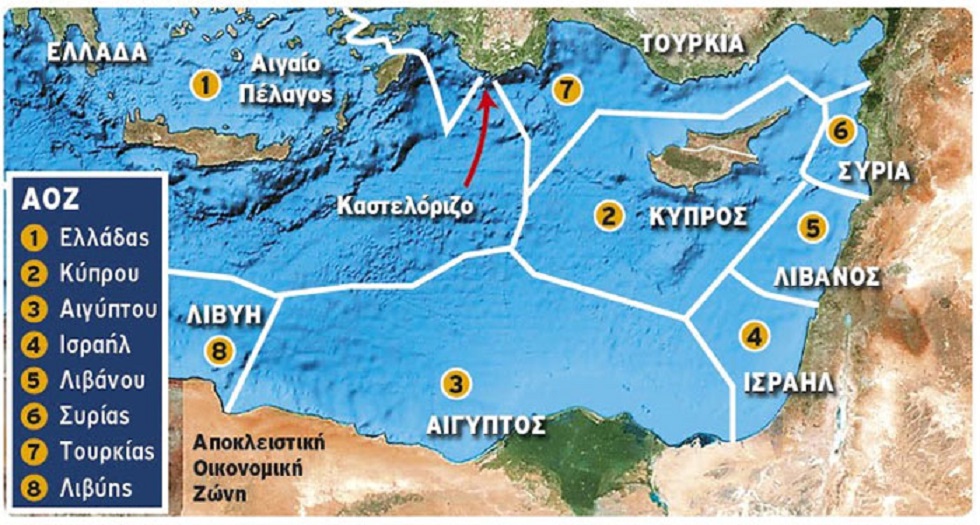

Located in the northeast corner of the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus has access to some of the most important sea lanes and chokepoints in the region, including the Bosporus and the Dardanelles (the main arteries connecting the Mediterranean to the Black Sea) as well as the Suez Canal (the gateway to the Bab el-Mandeb strait and Indian Ocean). The Kyrenia and Troodos mountain ranges, which surround the capital city, Nicosia, and the country’s coastal lowlands make Cyprus an easily defensible island. It’s also a resource-rich island, with natural gas reserves, first discovered in 2011, worth an estimated $44.8 billion. It’s now part of the “energy triangle,” which also includes Israel and Greece, and the EastMed pipeline project to bring natural gas to European markets.

Although it measures only 3,572 square miles, the island’s location and natural resources have made it a target for ambitious neighbors and rival powers. The Greeks, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Romans, Persians, Achaemenids, Macedonians, Byzantines, Ottomans, Venetians, British, Turks, Russians and Americans have all sought to gain a foothold in Cyprus, recognizing the strategic depth it offers, particularly when it comes to protecting access to sea lanes and projecting influence in the Mediterranean and beyond. But all these powers have been driven by different imperatives.

For Anatolian powers, Cyprus acted as a buffer between themselves and the Greek Aegean islands and southern Europe, as well as a launchpad for naval operations in the Western Mediterranean. Control over Cyprus allowed powers like the Ottoman Empire to become major naval powers that even rivaled the Portuguese for a time and to establish greater territorial control in Africa, the Gulf and the Balkans.

For Western powers like France, the U.S. and Britain, Cyprus has served as a hub to support military operations in the Middle East and North Africa, protect imperial assets in the region and counter Russian naval power. During the Cold War, Cyprus served as the West’s regional headquarters for intelligence on Soviet activity in the Middle East and Arab states. It also helped access chokepoints important to Europe and was used during Britain and France’s 1956 amphibious invasion of Egypt.

Russia’s interest in Cyprus stems from its imperative to establish warm-water ports along the Mediterranean. Although Russia has never controlled any part of the island, it has forged close economic ties there.

Divided Island

Cyprus’ population, therefore, is the product of centuries of shifting control. Cypriots in the southern half of the island speak Greek, while those in the northern half speak Turkish. In terms of religion, the population is a mixture of Greek Orthodox Christians and Sunni Muslims. Though its demographic diversity has made the island adaptable to frequent political changes, it also made the population vulnerable to outside influences. In fact, throughout its history, Cyprus has never experienced genuine autonomy. It became independent in 1960, but only on paper. The Treaty Concerning the Establishment of the Republic of Cyprus, which established Cyprus’ independence, and the Treaty of Guarantee barred the island from uniting with another state and entrusted defense of its independence to the signatories of the treaties: Greece, the U.K., Turkey and Cyprus itself. The U.K. managed to retain two bases in the country at Akrotiri and Dhekelia along 98 square miles of sovereign territory, which could be used for intelligence gathering and logistics and as a staging ground for military operations in the Middle East and North Africa.

The competition between the guarantors reached a peak in 1974, when the Greek military junta organized a coup that was carried out by the Greek army and Cypriot National Guard against Cypriot President Makarios III. Turkey responded by invading the island on the basis that it had a duty to defend Cyprus’ independence. The result was the partitioning of the island and formation of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

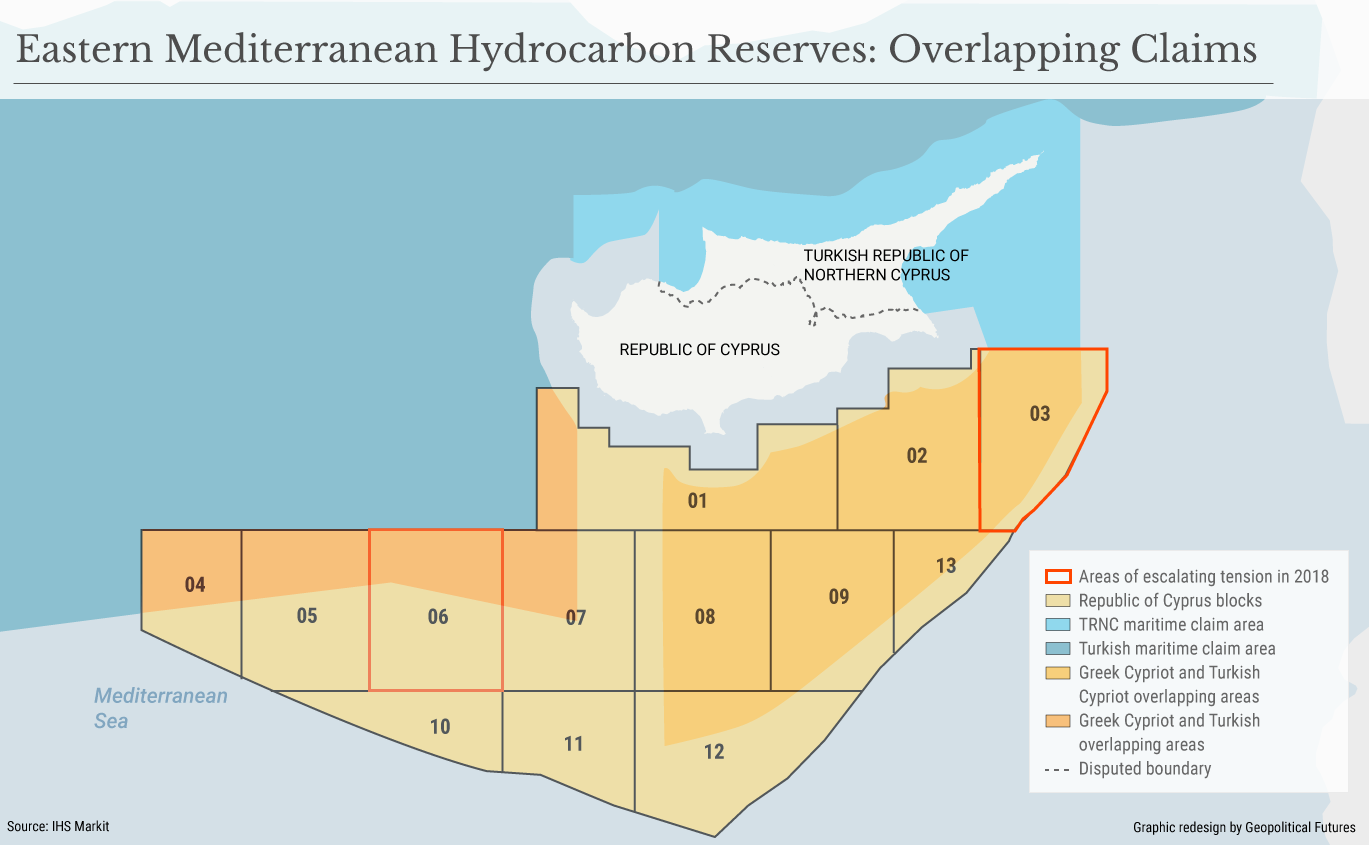

Cyprus remains today a frozen flashpoint in the Eastern Mediterranean, divided between the pro-Greece Republic of Cyprus in the south and the pro-Turkey TRNC in the north. Both Athens and Ankara see Cyprus as a buffer and are determined to prevent the other from controlling more of the island than it already does. Although Turkey is the only country that recognizes the TRNC, its key role in Mediterranean affairs can’t be denied. It’s through the TRNC that Turkey has managed to reestablish the influence the Ottomans once had over the island, in the hope that Ankara can increase its commercial, naval, economic and political power in the region. And Turkey has used its connections to the TRNC to defend its hydrocarbon exploration and drilling activities off the coast of Cyprus – which the Greek Cypriot government sees as a violation of its sovereign rights. Ankara has also used its foothold in the north to increase its naval presence in the Mediterranean, which it has used to monitor sea lanes and support its military operations in Libya and Syria.

Greece, too, has leveraged its influence over the island to advance its regional strategy. Since Cyprus became an EU member in 2004, Greece has used the Cyprus issue to block Turkey’s accession into the EU and to drive a wedge between Ankara and Brussels. It’s fearful of what a Turkish-controlled Cyprus would mean for its maritime claims, energy projects and control over islands in the Aegean Sea.

Beyond the Greek-Turkish Rift

Certainly, the Cyprus issue continues to define Turkish-Greek relations. But the island is also at the center of other issues in the region. It has become a pivotal launchpad for Western intelligence, military and counterterrorism operations in the Middle East. British bases in Cyprus have turned into a portal from which the U.S. and NATO can launch air missions, monitor electronic communications, signals intelligence and naval operations. It has also participated in joint naval exercises with NATO members like France, Italy and the U.S. in the Mediterranean. Cyprus has even signed a bilateral defense cooperation agreement with France, expanding its Evangelos Florakis naval base to host French warships. To counter these efforts, Russia is also trying to increase its influence on the island. In the mid-2000s, for example, it provided billions in loans to Cyprus. Russia has become one of Cyprus’ top sources for foreign direct investment, a well-placed expense considering that Moscow receives 26 percent return on its investments in Cyprus. The relationship between the two countries has meant that Russian vessels can patrol Cypriot waters mostly without interference and Russian warships can use Cypriot ports to support ongoing military operations in Syria and Libya and to keep an eye on U.S. and Turkish activities in the region.

With new discoveries and shifting national priorities, the competition over Cyprus has evolved over time. But the dynamics within Cyprus have more or less stayed the same: It remains a small, fragmented island, fought over by actors seeking to expand their strategic depth in the Eastern Mediterranean.

ΠΗΓΗ: Geopoliticalfutures.

Ta ενυπόγραφα κείμενα απηχούν τις απόψεις των συγγραφέων τους